Organistrum: new polyphonic keyboard

My reconstruction of the instrument is mainly based on my own interpretation of its possible musical function. Since I want to consider it as a genuine polyphonic instrument I invented a special keyboard, fit for 12th century two voices polyphonies, suggesting also a different managing of the wheel.

Keyboard

By tuning the strings either: A – d – a or: A – e – a we get an overall extension of two chromatic octaves (minus the last semitone). Before lifting each key, the performer can choose which string he is going to touch, simply by turning the key to the proper position: the first one allows him to operate on the bass string, the second on the middle one, the third on the higher string.

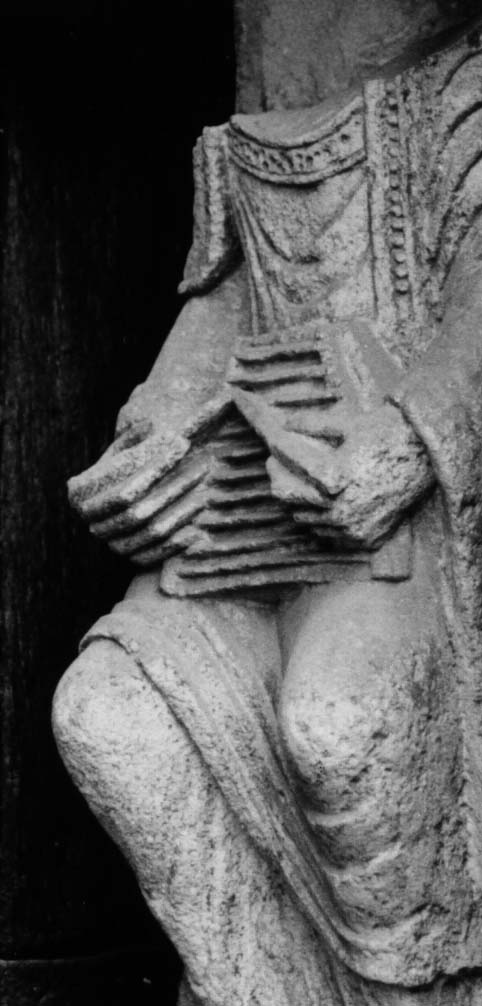

Thus it is possible to play two different melodic lines simultaneously. In Santiago sculpture the hands of the musician on the right are on the third and on the fifth key. This means he is playing -c, g - rather than -d, f - bichord on bass and middle strings, or - g, c’ rather than - f, d’- bichord on middle and higher strings (first tuning).

First string a.. a# b c’ c’# d’

Middle string d.. d# e f f# g

Bass string A.. A# B c c# d

Keys 0 1 2 3 4 5

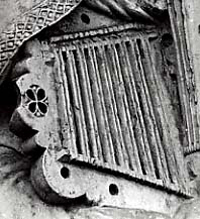

In position 4 the key is provided with two tangents so as to act on second and third strings (tuned either in Fifth or Fourth) at the same time to perform Organum parallelum, leaving the bass string as a drone.

How they calculated the semitones progression

Known medieval texts neither describe nor discuss about the possibility of a chromatic scale. But, reading Boethius's De institutione musica, easy to be found in monastic libraries since 9th century on, the monks could learn a lot about semitones both from pythagorean tradition and from Aristoxen's. There are only few lines, but enough, dedicated to the description of Aristoxen's practical method to divide the monochord. From this source the medieval scholar could learn a practical method in order to draw a correct chromatic scale of 12 tempered semitones. We discuss about this in this article:

connecting astronomical and musical knowledges through 10th and 12th centuries. Anyway, this idea comes from very early roman sources: Plinius and Boethius. In case the author of Santiago instrument intended to describe a revolutionary full chromatic/polyphonic keyboard we can suppose he was aware of that very ancient tradition.

Wheel

On the other side, the musician who is in charge of turning the crank, by a smooth, even movement of his right hand, can also lift one or even two of the strings from the edge of the wheel with his left hand in order to stop them vibrating. This way you can either avoid conflicts between the voices or stop undesired drone effects.

LISTEN TO POLYPHONIC SYMPHONIA:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UpZP62BPVGY

BOOKS:

BUILDING A REPLICA OF SANTIAGO DE COMPOSTELA INSTRUMENT

I chose one big Red Willow (Salix purpurea) planck, seasoned in nature, from which I carved the sound box and the base of the keyboard in one piece, average thickness 8-10 mm. Flat back, flat sides as in the original.

GENERAL MEASURES:

Total length 940mm

Max width 230mm

Depth 80mm

Diapason 720mm

In the bottom of sound box I drilled a 10mm hole for the wooden axis, made of Beech (Fagus silvestris). Axis ends into another hole of 10mm drilled directly with no axle box in a wooden bar (Spruce) 15mm thick, glued between the two lobes of sound box which has been carved out of one piece of Spruce (Picea abies) 8mm thick with no other bars glued underneath. Keyboard box is independent from the body of the instrument and can be easily removed to modify general level of the bars, changing their angle with the strings or making reparations. The 11 bars of the keys, diameter 10mm, are of Pine (Pinus nigra) and the 55 pivoting tangents of Beech. The problem of the distances among the bars is discussed in the present article. To avoid noise made by the bars returning to their previous position, after being pulled up to play, a stripe of cloth has been glued at the bottom of the keyboard. The carved lid has been made of Spruce, 8mm thick and is simply interlocked with the body of the keyboard without any hinge or other device.

The wheel, 11cm wide and 20mm thick is of Walnut (Juglans regia) and forced on wooden axis without any screw, nail, or wedge. No axle box at the end. The Beech crank , stuck in the square end of the axis, can be easily removed. The soundboard is glued to the body of the instrument , no sound pole in it. The bridge is of Poplar (Populus nigra) reinforced with a Beech edge. The tailpiece of Chestnut (Castanea sativa) is linked to the bottom of sound box by a leather lace. Tuning pegs are of Beech, no need for a tuning key. Two light layers of pure almond oil have been used as finishing . Gut strings: 0.80, 1.10, 1.40mm.

Read more:

https://ojs.unito.it/index.php/archeologiesperimentali/article/view/8489